Sometimes a picture idea gets aborted after a lot of work. That happened with a picture I developed 25 years ago for National Geographic.

The idea was to show Neolithic humans in their first domestication of sheep. This was to be for an article on wool. The archaeological evidence seemed to point toward a scenario where mouflon sheep were captured, penned in, and controlled.

After doing many thumbnail sketches, the art director and I agreed on a scene where two men are restraining a ram while the ewes are released from a cave. I made a little clay maquette of the scene (photo, inset) to work out the lighting, and then did a charcoal drawing of the light and dark masses.

Then I hired models come into the studio and had them pose for charcoal studies. I wanted to use the really old-school method of working from studies rather than photography. I also went to the Bronx zoo to do sketches of mouflon sheep.

The next step was to work up the scene in color. I was getting excited by the opportunities with lighting. The view expanded outward to show more of their camp, a kid with a lamb, some hunting trophies, and the far landscape vista.

But wait! The archaeologist and the magazine art staff had additional ideas. How about a dog, and an old man? Maybe we could show more of the fence and how it was made. I kept redrawing it.

Eventually the picture lost momentum. I think we all became conscious that this one picture was trying to accomplish too much. There were too many ideas in it. As Howard Pyle said, it is essential that a picture express just one idea. "If in making a picture you introduce two ideas, you weaken it by half—if three, it weakens by compound ratio—if four, the picture will be really too weak to consider at all and the human interest would be entirely lost."

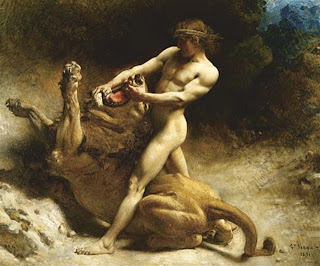

If I just showed two guys wrestling a ram, that might have made a great picture. That simplicity is what makes Leon Bonnat's painting of Samson wrestling the lion really memorable.

Also, the editorial focus of the article changed, the layout space shrunk, and we decided to go with a completely different picture, showing the range of wool-bearing animals. National Geographic was a good client, and they paid me for the time I put into it.

Even though every picture is a labor of love, and you put everything into it, one has to be philosophical when this happens. This kind of abandoned work is fairly common when you work for clients that must balance a lot of different considerations, or that have a lot of decision-makers, or that are working with large financial stakes. Anyone who works in movie concept art and theme park design has similar stories.

--------

Check out the new book on Howard Pyle, with my article on his thinking and process.

The wool-bearing animal picture appears on page 36-37 of Imaginative Realism

No comments:

Post a Comment